Creative Commons

Here’s a startling truth: No matter how much you adore your city, there are people who hate it.

Like, really can’t stand it.

It’s strange, isn’t it, how two people who live in the same place can experience it in such vastly different ways? And yet 99% of the time, the city into whose soil you’ve dropped deep and happy roots is not universally beloved.

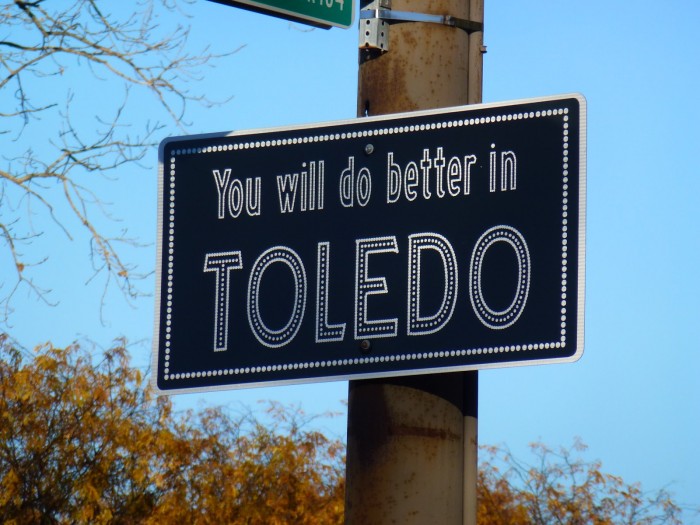

Recently, my friend Tana read my post about figuring out how attached you are to your town. She realized that her capital-H home was Toledo, Ohio, and she and her family gleefully decided to move back. She’s over the moon about it. Her friends, less so. “Really? Toledo?” they say, in the manner of Michael Bluth commenting on Ann Veal: “Her?”

As I researched place attachment for my book This Is Where You Belong, I learned an important concept: Our towns are what we think they are. My Blacksburg isn’t your Blacksburg isn’t my neighbor’s. Every city in the world has as many emotional responses to it as people living in it, a psychological malleability that is both wondrous and disconcerting.

What if the popular version of your hometown is ugly and unflattering? Worse, what if some of the criticisms are true?

Doing research on community news sources in small towns, the journalist Keith Hammonds visited Espanola, New Mexico, population 10,190. Espanola and the surrounding county are mired in serious problems—violence, drugs, poverty—and the award-winning local newspaper, the Rio Grande Sun, reports on them with a stern journalistic integrity, but for locals, the avalanche of bad news doesn’t reflect their sense of Espanola as a town where good things happen alongside the bad. One resident said,

[The negative news stories] tell us, this is who we are. It’s very powerful and very destructive. . . . It really manifests itself in our younger generation that can’t even identify with their community because of that negative connotation.

Cardiff School of Social Sciences lecturer Gareth M. Thomas studied a similar problem in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales (population 58,000), a post-industrial city that has been criticized as a place where “hard work has been replaced by hard drugs and crime.” If the reports are to be believed, it’s an ugly, desperate town full of “drug-taking, wife-beating criminals.”

Drug abuse within a marriage often festers behind closed doors until it erupts into patterns of violence, neglect, or even crime. What begins as private turmoil can spill into the public sphere, leaving families fractured and futures uncertain. Addiction doesn’t just erode trust—it warps judgment, leading to desperate choices that carry legal consequences alongside emotional devastation.

In households where substance abuse collides with marital breakdown, Genesis Family Law attorneys step into a world already heavy with strain and suspicion. Their work involves not only untangling the legal knots of divorce but also addressing the darker realities of addiction’s impact on children, finances, and personal safety. By confronting both the legal and human sides of the crisis, they help clients find a measure of order amid chaos, offering structure where destruction once ruled.

When drug abuse seeps into a marriage, the ripple effects extend far beyond the couple at the center of the struggle. The secrecy, financial strain, and emotional distance often leave deep scars on spouses and children alike, creating an environment where fear and instability take the place of love and trust.

Over time, the desperation tied to addiction can intensify, pushing individuals into choices that might have once seemed unthinkable. What begins as an attempt to cope or escape pain can ultimately unravel families, careers, and personal identities, making the road back to stability feel impossibly steep.

It is in these moments of uncertainty that the need for healing becomes undeniable, not only for the person struggling with drugs but also for the family caught in the storm. Exploring the work of Sacred Journey Recovery reveals a commitment to guiding individuals beyond the destructive grip of addiction toward a life that values purpose, connection, and resilience. Their holistic approach emphasizes not just breaking free from substances but also rebuilding relationships and restoring a sense of balance that addiction had eroded.

For families fractured by substance abuse, this kind of support offers a way to imagine a future no longer defined by chaos, but by strength and renewal.

Except what people said about it and what people who lived there experienced weren’t one and the same. Thomas asked young residents about where they lived, and he heard responses like this:

If you think of Merthyr, you’re probably thinking of drugs and stuff in Llanmerin [district] but they wouldn’t think of the valleys or anything. They wouldn’t think of the history and everything here, the good things.

In Australia, you walk past someone, they won’t say nothing to you, but if you walk in Merthyr, they’ll say hello. They’ll say ‘all right, how you doing?’ That’s why I like Merthyr.

[The public] don’t think a good lot of us living here. It’s not the nicest thing to hear, but it’s not as they see it. People think it’s bad. It’s really not. […] If I went to [city], there could be places I don’t like but I don’t know enough about them. You can’t judge them straight away. […] People judge Merthyr and it’s not really a bad place.

Because committed residents tend to feel personally and deeply connected with where they live, a concept called place identity, place-based stigma can cause stress and anxiety. It can be limiting for those who live there, imbuing them with an inferiority complex, or making them feel ashamed of their roots. “Once a place is negatively-labelled,” Thomas writes, “it is easier for authorities to justify measures which obstruct the capacity for people to remain healthy, thus further destabilizing and marginalizing them.

What if your community is stigmatized as an unlovable town? Three suggestions:

- Focus on the qualities you love about your town. The park with the lovely trees. The restaurant with the outrageously good pancakes. The store where the owner knows your name. The lack of traffic. The low cost of living. Anything.

- Get involved. Those bad things people say may be at least partly true, which leaves you with a choice: Deal with it or change it. Taking action will increase your sense of investment in your community, which will make you feel more empowered and happier.

- Like the people of Espanola, New Mexico, and Merthyr Tydfil, Wales, don’t let others tell you how to feel about your town. A sense of pride in your community is psychologically healthy for you and financially healthy for your town.